Stories / Asia / Tibet |

||||||

Seven Days in TibetOn the road from Kathmandu to Lhasa, Martin discovers that the modern Tibet is a fascinating land of contrasts where nightclubs outnumber monasteries and nomads carry cell phones.by Martin WierzbickiThe Friendship Highway is definitely not a highway. It's hardly even a road by most definitions, but a rough dirt track that begins in Kathmandu, traverses the steep terraced valleys of Nepal, climbs over the highest mountain range in the world, the Himalayas, weaves through the desolate high-altitude desert of the Tibetan plateau, and ends in Lhasa, the mythical capital of Tibet. It takes a week to make the thousand-kilometer journey, sometimes driving as much as twelve hours a day. Our Tibetan guide (let's just call him Tashi to keep him out of trouble with his wife) met us at the border with Tibet. Striding around confidently with an air of authority, he seemed to know all the officers at the border, as well as every official in every town between Lhasa and Kathmandu. Surprisingly for a guide, Tashi showed little enthusiasm for explaining the sights that we passed. But he showed plenty of enthusiasm for talking about himself (especially with some of the women in our group).

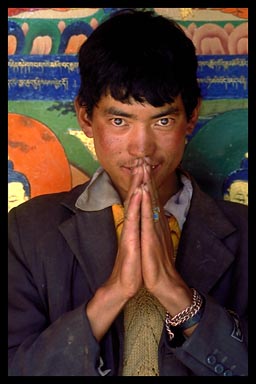

During the long days on the road, I had plenty of time to get to know the other travelers in our group. Andy was a young, successful currency trader from London who got ripped off by an equally successful Chinese moneychanger at the border, exchanging British Pounds for Chinese Yuan at half the official rate. He also had an insatiable curiosity, firing a never-ending series of questions at our guide, to which he usually received a less than satisfactory response. "Tashi, how high is that mountain?" ("I don't know.") or "Tashi, why is the color of that lake turquoise?" ("Minerals.") When he wasn't questioning Tashi, Andy spent most of his time talking to Javier, a technology consultant from Madrid with a particular aversion to Tibetan food. "Fried rice with vegetables or friend noodles with vegetables?" It was the same choice every night. "Paella! I want paella," he protested fruitlessly. Nathalie had a passion for piano, teaching piano lessons to a handful of students in her native France. She wore her hair in girlish braids and spoke with a French accent that transformed everyday items into erotic sexual objects. "Can I have your penis?" she asked once, gesturing toward a bag of peanuts. Her passion for piano was matched only by her passion for Tibetan men. While the piano wasn't a common instrument in Tibet, remarkably Natalie finally found happiness in the arms of a young Tibetan piano student she met at disco in Lhasa. Meanwhile, Jim and Gaby spent the long days on the road in deep philosophical discussions. "Is there such a thing as a selfless act?" was one of the many existential questions they debated. —————— As I pondered these and other philosophical questions, I watched the desolate landscape of the Tibetan plateau drifting backwards outside my window. In the soft evening sun, the barren mountains and valleys glowed in highlights and shadows. Nomads wrapped in filthy coats of leather and fur wandered the dry grasslands with a handful of sheep. Tiny villages lay scattered along the valley floor with plumes of smoke rising from medieval stone houses. Some of the villages were protected by walls covered with hand-pressed yak manure. In the dry wasteland of the Tibetan plateau, where natural resources are scarce, even this waste product is recycled, dried and used as fuel.

We shared the road with mule carts and tractors. Occasionally, we passed a run-down truck that choked and sputtered as it climbed a high-altitude pass, overflowing with a hundred dusty faces in the back. They smiled and waved cheerfully as we passed. For many Tibetans, this was still the only form of transportation between remote towns. Life wasn't easy in the back of a truck, but in the minibus we had our own problems. Five kilometers above sea level on the Tibetan plateau, the atmosphere contained only half the oxygen of lower elevations, leaving my lungs gasping for air and my head throbbing—the first symptoms of AMS, or acute mountain sickness. To help our bodies adjust to the altitude, our guide encouraged us to drink water—a lot of water—which created another interesting dilemma. [ next page | Where do you go to the bathroom in the barren steppes of the Tibetan plateau? ] |